Assistant Professor Ieva Lībiete Will Speak at the COVID-19 Conference About How Pandemics Historically End

COVID-19 is not the first pandemic in history and is unlikely to be the last, which is why it is important to understand the historical aspects of pandemics.

Ieva Lībiete (pictured), Associate Professor and Head of the Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU) Anatomy Museum, will speak about this at the international COVID-19 conference Impact, Innovations and Planning on 28–29 April.

Why is this topic important?

At the conference, I will look back at the history of medicine and try to answer a question that is relevant today: how do pandemics really end? How do people decide when an epidemic in a particular place is over and when can they return to normal life? This is a little-studied topic in the history of medicine, as most researchers have been interested in how epidemics start, how they spread to the scale of a pandemic, and how society has historically reacted to them. Very few researchers have looked into how pandemics end. This is largely due to a lack of historical sources, as people stopped writing about it during the decline of epidemics.

What have been the most devastating pandemics in history?

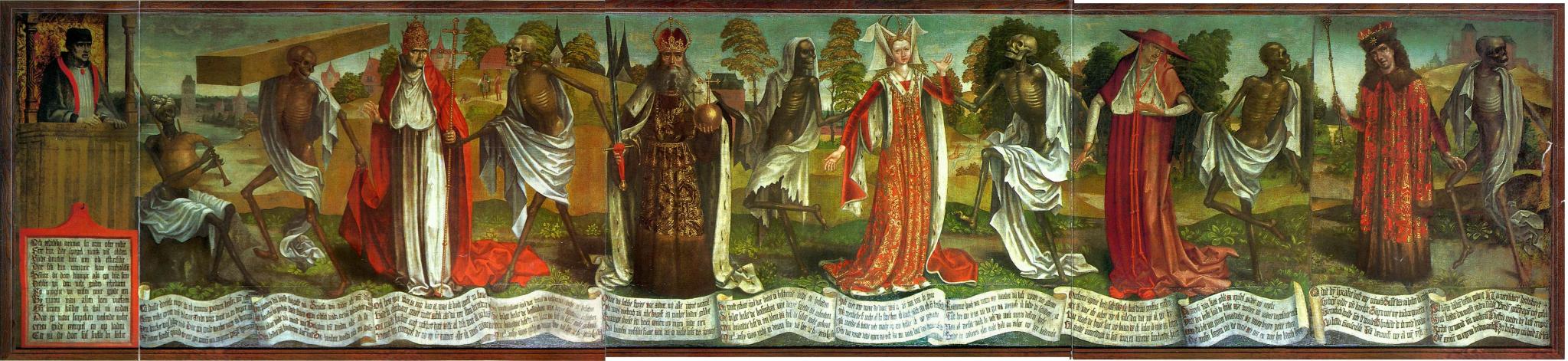

Traditionally, the plague in the 14th century, more commonly known by its Gothic name “black death”, is considered the most devastating. It is estimated that an average of 30–60% of the entire European population may have died during this pandemic, which lasted from 1346 to 1353. Some historians believe that the pandemic contributed to the collapse of feudalism and even to the Renaissance. This epidemic has left its mark not only on the history of medicine, but also on literature and art. Mortality numbers were so high and death was so present in everyday life that the Danse Macabre genre of art (or Dance of Death) emerged at that time. This allegorical genre highlighted the universality of death in literature, music or visual arts and spoke of the procession of the living and the dead in which the living are ranked according to their social status. A striking 17th century example of this genre can be found pretty close to us, as a fresco in Tallinn’s St. Nicholas Church.

'Danse Macabre' by Bernt Notke

Can you give an example of how a pandemic can end?

I find it useful to distinguish between biological and social pandemics, where a biological pandemic is a certain biological reality, and a social pandemic is society’s response to that biological reality. And these pandemics – social and biological – do not always coincide and overlap. Strictly speaking, in the biological sense, there has been only one pandemic that can be considered completely over: black pox caused by the variola vera virus that was completely eradicated in the late 1970s. More often than not, the end of a pandemic is considered to be the point at which incidence rates drop to endemic levels, when society accepts a disease as part of everyday life and learns to live with it. One thing is clear from medical history: epidemics and pandemics have never ended suddenly, and this has always been not only a biological and medical decision, but also a social and political one.

How could knowledge of the history of pandemics help us to cope with them today and in the future?

We cannot easily draw parallels between epidemics of the past and today, if only because the world we live in today is very different from what it was during the plague, the black pox, or even the relatively recent Spanish flu. This is what I say to my history of medicine students: knowing the history of medicine teaches us humility and helps us to be critical of contemporary developments in a healthy way.

Related news

Improving patient-centred care: RSU researcher attends Health.Tech Summit in SwitzerlandResearch, Public Health

Improving patient-centred care: RSU researcher attends Health.Tech Summit in SwitzerlandResearch, Public Health