One sweet day a week, fluoride toothpaste, and a personal dentist… RSU dental researchers’ recommendations for oral health

Writer: Linda Rozenbaha, RSU Public Relations Unit

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Brushing alone is not enough to protect against cavities – using fluoride toothpaste is essential for effective protection. Other types of toothpaste serve merely a cosmetic purpose, not a therapeutic one. Although even children are taught about the harmful effects of excessive sugar consumption on teeth, there are still many untapped opportunities to improve public health – both at the individual and family level, as well as nationwide.

Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU) researchers share their insights into both the well-known and lesser-known aspects of oral health in Latvia – from lifestyle habits and public knowledge (or lack thereof), to the lingering impact of the Soviet healthcare legacy. Ilze Maldupa, leading researcher and lecturer at RSU’s Faculty of Dentistry, and Dr. med. Sergio Uribe, Associate Professor and senior researcher at the Department of Operative Dentistry and Oral Health, offer their perspectives. Dr Uribe, originally from Chile, provides a unique outsider’s view.

You have conducted extensive research on children's oral health, which reveals that Latvia ranks among the lowest in Europe in terms of child oral health indicators...

Ilze Maldupa: Yes, in 2015, we found that 98.5% of 12-year-olds showed signs of tooth decay. This means that only 1.5% had completely healthy teeth. In 2023, the results were slightly better: nearly 14% of 12-year-olds and 7% of 15-year-olds in Latvia had healthy teeth. However, due to the level of public engagement, we’re not entirely sure if this improvement is genuine or if the study simply included children with generally better health. Overall, we can confidently say that

at least 70% of Latvian adolescents have visible tooth decay — a figure that is the reverse of what we see in Scandinavian countries, where the majority of children are caries-free.

In other words, when it comes to the prevalence of cavities, Latvia is roughly where Scandinavia was in the early 1980s.

What did Scandinavian countries do to significantly reduce caries rates?

Sergio Uribe: Prof. Ole Fejerskov from Aarhus University once said, ‘What we achieved in the 1970s could not be done today.’ Denmark succeeded in raising an entire generation free from caries.

Ilze Maldupa: They used several methods, each with varying levels of effectiveness, but three in particular likely had the greatest impact. First – the “sweet day” tradition. In Scandinavia, Saturday is a day when the whole society follows the rule, and children are allowed sweets only once a week. Second – ensuring that families had access to fluoride toothpaste. And third – the routine application of sealants in dental clinics.

Meanwhile, during Scandinavia’s “oral health awakening,” we were living through the Soviet era. Can the current situation in Latvia partly be explained by this legacy?

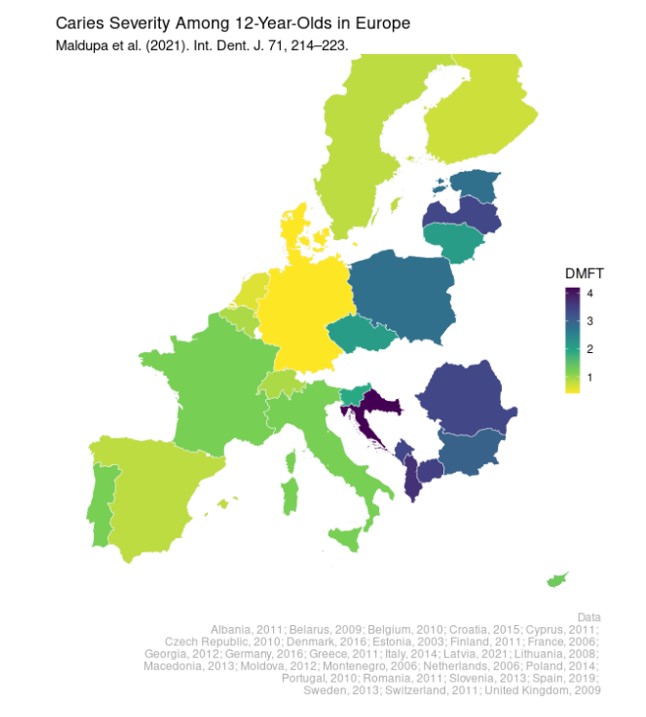

Sergio Uribe: We compiled data from across Europe (as shown in the accompanying map), and it clearly shows that the closer you get to Eastern Europe, the higher the prevalence of caries. So, there must be a connection. One major factor is likely dietary habits – a high intake of ultra-processed foods, including those rich in sugar. Cultural differences also play a role. In many cases, there is an expectation that someone else will take responsibility for the child’s health, meaning the role of the family is diminished. Another factor – in Scandinavia and other parts of the world, evidence-based methods are being introduced to detect and treat caries at an early, subclinical stage. In Latvia, the implementation of such practices has been slower.

Ilze Maldupa: When it comes to cultural differences, one thing we observed during the research process—especially after the COVID-19 pandemic—was a notable resistance from society. Schools and parents were reluctant to allow children to participate in the study. I interpret this as a lack of understanding of one's role in contributing to the greater good of society. As Sergio pointed out, during the Soviet era, parents were conditioned to believe that their children essentially belonged to the state, which would take care of them—deciding when they should eat, how they should exercise, what they should learn, and where they should eventually work. They didn’t have to think for themselves.

This mindset fostered a generation of people who wait for someone else to take care of them—ideally, at no cost. At the same time, the “Iron Curtain” suddenly fell, and with it came an unbounded freedom. As many have pointed out: in a healthy society, an individual’s freedom ends where another person’s rights begin. But here, this concept is often forgotten, and people don’t feel responsible for others. Sometimes it even seems like there's a sense of hopelessness in our society—an attitude of “things won’t improve anyway, so why try?” This way of thinking could at least partly explain the poor state of oral health.

You also studied evidence-based methods for oral health prevention and treatment. What are the three most important modifiable factors for improving children’s and adults’ oral health?

Ilze Maldupa: I’d like to begin with children because they are the future adults.

The most effective step would be to protect our youngest from industrially processed foods—including so-called “baby food”

(except for infant formula). The labels indicating age suitability are primarily marketing tools and often have little to do with actual health impacts. Ideally, such foods should be avoided until at least the age of three.

This includes commercially produced purées, cereals, teas, juices, syrups, even homemade fruit smoothies, apple juice and other fruit juices, jam, and honey. Not to mention sweetened yoghurts, strawberry and chocolate milk, breakfast cereals, ice cream, sweets, and biscuits. We discussed the effects of sugar consumption at the RSU Research Week 2025 scientific conference together with representatives from various Latvian ministries. Reducing sugar intake early in life could not only lower the prevalence of tooth decay, but also reduce the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer—creating a significantly healthier population.

Sergio Uribe: Nutrition is the most important factor in effectively controlling the spread of tooth decay.

But coming from Latin America, I was shocked to learn that drinking water in Latvia is not fluoridated, even though the prevalence of caries is so high.

Water fluoridation is the most effective measure available—and it doesn’t require active participation from the public. Until that changes, it is especially important to ensure fluoride intake through toothpaste.

Ilze Maldupa: We’ve investigated how many people in Latvia actually use fluoride toothpaste, and unfortunately, the numbers—especially among children—are not encouraging. Among preschool-aged children, fewer than 40% theoretically use toothpaste with the recommended level of fluoride. I say “theoretically” because not all children who have fluoride toothpaste at home use it every day, and not all toothpastes that claim to contain fluoride actually have it in an active form. We’ve started researching this and hope to soon be able to inform the public about the most effective products available in the Latvian market.

Should parents be looking at the fluoride levels in toothpaste for children? For example, my five-year-old’s dentist recommended toothpaste labelled for older children...

Ilze Maldupa: Yes, the age indicated on toothpaste packaging is determined by the manufacturer and often has no real connection to clinical indications. Toothpaste is classified as a cosmetic product rather than a medicine, so in theory—like with shampoo—you can choose based on appearance and scent. However, due to the added fluoride, toothpaste could be considered a therapeutic product. But because toothpaste has historically been categorised as a hygiene item—and because of the relevant legislation—we currently don’t have the tools to distinguish whether a toothpaste is just cosmetic or whether it truly protects against cavities.

You once mentioned in an interview that brushing your teeth with any toothpaste that doesn’t contain fluoride is essentially useless (!?). Could you please elaborate? Also – during the Soviet era, fluoride tablets were recommended. Is that an outdated method?

Ilze Maldupa: People have been cleaning their teeth since before the Common Era, but since the advent of agriculture – and even more so after the Industrial Revolution – the prevalence of tooth decay has significantly increased. Brushing teeth, meaning mechanically removing plaque, does not protect against caries. The first decrease in caries prevalence in human history was achieved through water fluoridation, though at first, the mechanism of fluoride was not fully understood. It used to be believed that saturating the teeth with fluoride during their development would make them stronger for life. Countries that could not fluoridate their water began using fluoride tablets – including the Scandinavian countries, from which we borrowed this idea. As I’ve said, not everything introduced in Scandinavia was effective. Meanwhile, in the 1970s, fluoride was also added to toothpaste, and by the 1990s it was entirely clear that fluoride toothpaste, like water fluoridation, could reduce the prevalence of caries.

Sergio Uribe: In the 1970s, fundamental studies showed that

in order for fluoride to inhibit caries development, it must be present in the biofilm around the teeth – that is, in the fluid surrounding the tooth – and not embedded in the enamel during development.

Fluoride incorporated into enamel does not prevent demineralisation. However, when fluoride from water or toothpaste is retained as a reservoir in the film around the tooth, it enables immediate mineral replenishment when pH levels in the mouth drop, thus inhibiting demineralisation.

Ilze Maldupa: Fluoride tablets were taken once a day, and they released very low fluoride concentrations into the saliva, which were insufficient to provide a preventive effect. Toothpaste must also contain a high enough fluoride concentration to be effective.

We can now continue discussing modifiable factors...

Sergio Uribe: A third modifiable factor is dental care. It’s evident that in Latvia, a healthy market economy does not function in this area, possibly due to free dental care for children – meaning parents don’t have to pay for their children’s treatment and may thus feel less motivation to take care of their children’s oral health. Another aspect is that due to the high prevalence of caries, there is little healthy competition among professionals, which discourages the adoption of new methods.

Ilze Maldupa: Moreover, there isn’t enough state funding for all children. However,

we’ve calculated that if evidence-based methods were used, it would be possible to provide care for all children in Latvia – ensuring that every child could visit a dentist at least once a year.

The results of this study were presented on 28 March during the "Research Week 2025" Dentistry Session.

As for adults – one of the most essential pieces of advice, in addition to diet and fluoride use, is to find a personal dentist and stick with them. Frequent replacement of fillings, even in Soviet times, often led to more serious complications. When I started practising in the early 2000s, I had many patients whose treatment had primarily taken place during the Soviet era. I observed that those with a fear of dentists often had either healthy teeth or only roots that needed extraction. Meanwhile, patients who had regularly visited dentists had teeth with large fillings and poorly treated roots – a condition that made the prognosis for those teeth significantly worse and treatment plans highly complex. Nowadays, a well-placed filling can last a lifetime. Of course, various factors can affect oral health, and there’s no need to worry if retreatment is necessary, but it’s better if your own dentist does it – they can assess the long-term prognosis more accurately if they know their patient.

I recently interviewed RSU tenured professor Shaju Jacob Pulikkottil from India, who spoke about his research in a poor Indian village. He concluded that the recommendation to eat meat to improve oral health would not be well received in a country where 70% of the population is vegetarian – it simply doesn’t align with their worldview. Instead, he found that encouraging people to brush their teeth twice instead of once a day was effective. In your view, what habits (due to mindset or attitudes) are difficult to implement in Latvia? And what tips are more promising?

Ilze Maldupa: Unfortunately, any advice is unlikely to reach the families who need it most. We recently discussed a case with colleagues – a girl who had changed foster families and care institutions multiple times.

Only at the age of 17 did a social worker take her to a dentist for the first time. Sadly, almost none of her teeth could be saved.

I believe this is not the fault of the girl or her family – it is society’s failure. In a developed European country, with the child under state supervision and entitled to publicly funded medical care, no one noticed that she was gradually becoming an oral health invalid. That’s why I support not just giving advice, but creating environments where such children can live as healthily as possible given their genetics.

Some advice is seemingly known to everyone. For instance, even my five-year-old daughter understands that sugar is harmful and damages teeth. Have you, through analysing evidence-based approaches to oral health, developed any methods or strategies for putting habits into practice that help reduce sugar consumption? What could be done to encourage behaviour change, and what political measures would help – for example, introducing a sugar tax?

Ilze Maldupa: You mentioned a crucial aspect of societal attitudes – everyone knows sugar is harmful, but they consume it anyway. Knowing is not the same as understanding. As long as we simply know that sugar increases the risk of disease – even when the risk is high, like a 36% increase for diabetes, 20% for heart disease, a third more for colorectal cancer, and a 40% higher risk of dying from that cancer – these striking statistics are often ignored unless people understand how sugar contributes to the risk. For example, if a parent understands that eating sugar attracts specific bacteria linked to poorer cognitive development in children, then upon seeing their child handed a caramel, they might imagine an increased autism risk. That parent will do everything to reduce their child’s sugar intake.

Sergio Uribe: People often misjudge risks due to cognitive biases and heuristics – mental shortcuts that lead to quick decisions. For example, people tend to seek immediate gratification: eating sweets to feel better or rushing to the dentist only when pain starts. In those situations, the problem already exists, so they seek a solution. But any risk of something happening in the future seems low. These short paths to immediate reward can lead to poor decision-making.

Ilze Maldupa: That’s why some decisions should be made at the political level, relieving individuals from having to make them alone.

A sugar tax is currently recommended worldwide; evidence shows it works to a certain extent.

In November, I took part in the adoption of the Bangkok Declaration in Thailand. Representatives from almost all countries, including several health ministers, participated. The declaration concluded that “there is no health without oral health,” and one of the key elements to address is sugar consumption. In Latvia, it’s a positive sign that the state has decision-making authority over food in schools and preschools. For children from financially and socially disadvantaged backgrounds, meals provided at educational institutions may be the only or most significant part of their daily diet. So with proper regulations, we could significantly improve public health.

* Mutes veselības pētījums skolēniem Latvijā (2023.) and Mutes veselības pētījums skolēniem Latvijā 2015./2016. mācību gadā

The full version of the article in Latvian can be found on the Delfi portal in Latvian

Source: Delfi.lv

Related news

Sports psychology study on young athletes: how burnout, anxiety, and wellbeing shape distinct athlete profiles Research, Psychology

Sports psychology study on young athletes: how burnout, anxiety, and wellbeing shape distinct athlete profiles Research, Psychology