RSU doctoral student Dana Dūda on the labyrinths of Chinese ideology and Latvia’s choice between business and values

Photo: Courtesy of Dana Dūda

Researcher and interpreter Dana Dūda is one of few Latvians whose professional and personal life has been deeply connected with China for a long time. Her experience includes studying in Shanghai, and living in Wuhan learning the language in an environment where foreigners often face restrictions on information. She also moved to Taiwan shortly before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Dana has mastered Chinese at a level that allows her not only to converse and interpret, but also to analyse Chinese Communist Party texts and ideological documents in the original language. This became the basis for her master’s thesis, and now, also for her doctoral research at Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU), supervised by Dr. Una Bērziņa-Čerenkova.

Dūda tells us about how China seeks to define and implement its worldview through the UN and international cooperation, and what this means for the security of our region.

Interpreter Dana Dūda at a Japanese diplomatic tea ceremony in 2024

Interpreter Dana Dūda at a Japanese diplomatic tea ceremony in 2024

You have been closely connected with China for a long time and know Chinese well. How did your interest in China arise?

My interest in China began at Riga Secondary School of Cultures, where I started learning Chinese with a fantastic teacher, Marija Nikolajeva. After graduating, I got a scholarship and went to Shanghai, where I studied the language for a year. Becoming a Chinese language specialist wasn't a deeply considered decision; at the time, I simply didn't know what I wanted to do in the future.

Back then, in 2014, there was a great deal of optimism about China in Latvia, and it seemed that new opportunities for economic cooperation would emerge.

There were five girls in our class who applied for the scholarship; three of us received it. I went to Shanghai Normal University with the intention of learning the language but soon realised that one year was not enough. My language skills were poor, and I needed to continue. Afterwards, I was sent to Wuhan – the city where Covid-19 later began. It was difficult, because there were not many foreigners around to speak English with, however, it was precisely because of this that I learned the basics of the language so well. In my third year, I returned to Shanghai and completed my bachelor’s programme in 2018.

What surprised you during your studies in China?

In China, we were not taught politics. History was embellished, and teachers avoided questions about Hong Kong or Taiwan. I was always interested in “sensitive topics.”

Books in English were available only on the so called “black market,” where foreigners exchanged them.

If someone had brought a book from home and read it, they could exchange it for new reading material with another foreigner.

I moved to Taiwan just before the pandemic, because China suddenly experienced an unusually severe virus season that no one could explain, as well as sudden political tensions. Right after the 19th Party Congress in 2017 and the enactment of the NGO law, state authorities started systematically target foreigners, considering them to be an ideological threat. Suddenly, the whole atmosphere changed. It was especially frightening for foreigners, as raids took place, and at times, it felt like you were seen as a problem just for being a foreigner. I felt that I had to leave.

How does China differ from Taiwan?

There’s a huge difference. The mentality in Taiwan is more Western. In China, life appears modern and impressive on the surface, but people’s thinking often seemed stuck in the 1950s. Paradoxically, however, life in China sometimes felt more Western because of international brands and the international culture. Taiwan, however, is not internationally recognised as a country, so it is more difficult for foreign companies to enter the market.

Compared to mainland China, there were significantly fewer foreigners in Taiwan. Still, you have to be aware that in mainland China you could be deported within a single day.

This is what happened with several Lithuanians I knew. Several Lithuanians were deported when Lithuania opened a representative office in Taiwan. They lost their visas, homes, and jobs. This shows how fragile a foreigner’s life in China can be. In Taiwan, everyone speaks Chinese, but the atmosphere is different. They use traditional Chinese characters, not simplified as in mainland China. It took some time for me to get used to, but eventually, I could “decode” them.

Taiwan does not recognise most bachelor’s degrees obtained in mainland China. As my bachelor’s degree was awarded in Shanghai by a university whose qualifications are not recognised by Taiwan’s Ministry of Education, I was not considered to hold a higher education diploma upon arrival. As a result, I enrolled in another bachelor’s programme in international business administration. This period coincided first with pandemic-related isolation measures and later with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.

It was then that I became interested in geopolitics, as I realised that business did not mean much if you did not understand the “big picture.”

After completing my bachelor’s programme, I obtained a master’s degree in international relations at Ming Chuan University, which is accredited in the US. In my master’s thesis, I compared the official Chinese rhetoric against Taiwan with Russia’s rhetoric against Ukraine. This research really fascinated and engaged me.

I realised that two years of research on China were not enough, so I enrolled in doctoral studies at RSU to continue my research work.

I was inspired by the research of Asst. Prof. Una Bērziņa-Čerenkova, Head of the RSU China Studies Centre. I am therefore very grateful that I can develop my doctoral thesis under her guidance. Bērziņa-Čerenkova is an excellent mentor and a role model. Moreover, RSU offers remote learning, which allows me to study while still living in Taiwan.

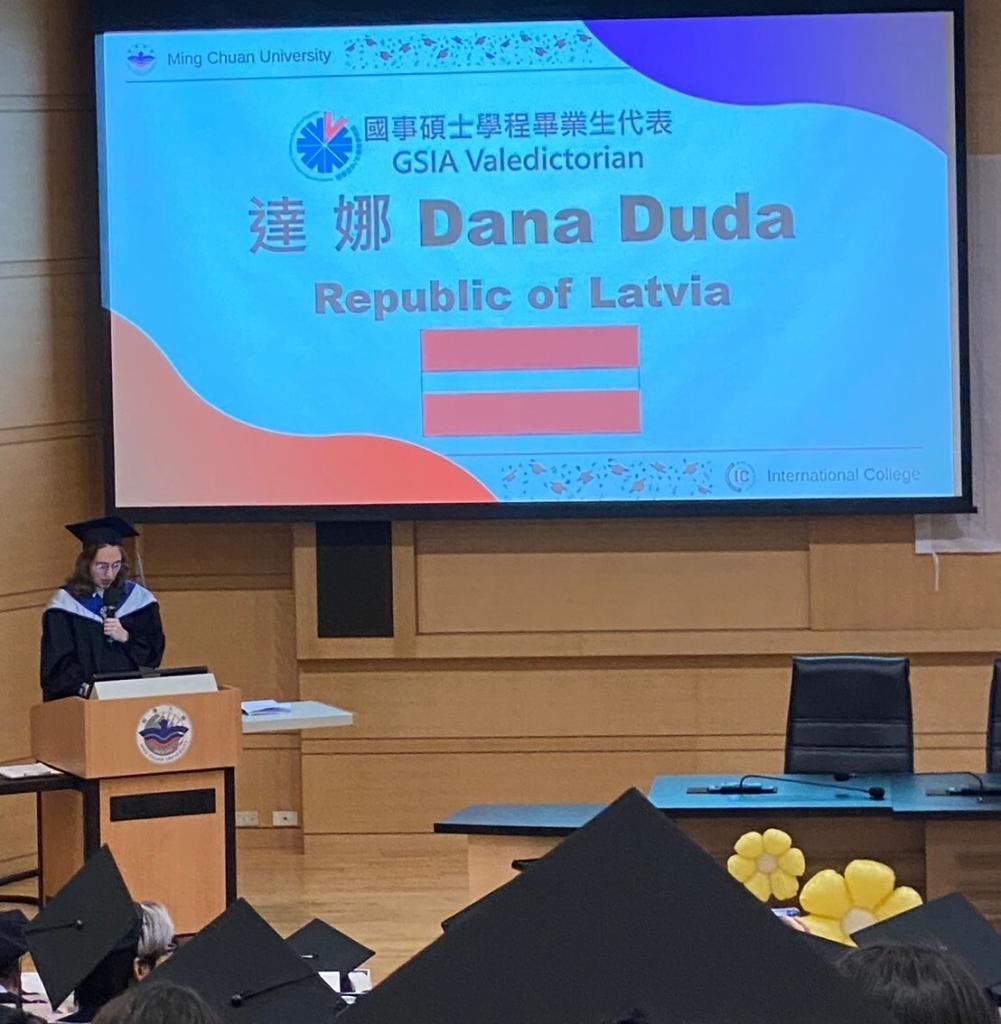

Dūda giving the valedictorian speech at the Ming Chuan University master's programme graduation

Dūda giving the valedictorian speech at the Ming Chuan University master's programme graduation

What do you want to explore in your doctoral thesis?

My research explores the official speeches and documents of the Chinese Communist Party, and the speeches of General Secretary Xi Jinping in particular. He has his own ideology, his own diplomacy, known as the Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. At the core of this political ideology is the concept of a Community of Shared Future for Mankind, which the Chinese leadership regularly uses and promotes in its diplomacy, including in Latvia. I first noticed it during my master’s studies.

When I started delving deeper, I realised that the concept is a tool that China is applying to try to reform global norms on world governance.

They do this through the UN and the institutions and initiatives they have established. The concept is very broad and designed to encompass the main spheres of global governance. Under each concept, there is an even broader hierarchical system. They are like the legs of an octopus, where each leg has more legs of its own.

My goal is to develop a glossary containing all these terms and definitions, explaining what they mean.

Even for native Chinese people, the language of the communists is completely incomprehensible if they have not studied the concepts of the Communist Party.

I would like to compare how China's interpretations differ from the liberal understanding of global governance. China uses words that are universally recognised and have positive connotations, such as democracy and values, but assign them a different meaning or definition. The problem is that this language finds its way into UN documents and is slowly changing the international language and understanding of liberal concepts.

At the master’s programme graduation ceremony

At the master’s programme graduation ceremony

Is this the new world order?

They call it a “reform” carried out through UN mechanisms, and in this way, China is seeking to become the new global rule-maker.

Russia also supports these ideas. On 9 May this year, Russia and China jointly signed a declaration on further strengthening cooperation to uphold the authority of international law. Paragraph 23 states that countries have the right to interpret international law according to their own understanding and that Russia and China invite other countries to jointly build a ‘community of shared future for mankind’. This signals shared strategic goals and, in my view, China–Russia solidarity poses a danger to Latvia.

For example, in the field of security, China regularly refers to concepts such as “legitimate security concerns” or “legitimate interests.”

This rhetoric is used to justify the idea that, under certain circumstances, countries can declare that they have such concerns regarding another country and therefore have the right to invade.

This is the way in which Russia justifies its invasion of Ukraine, which China supports through its rhetoric by stating that all countries must respect the “legitimate security concerns” of other countries.

The vision of a community of shared future for mankind is designed to ensure that all security issues are dealt with exclusively by the UN Security Council, while at the same time, China is unwilling to give up its veto power and extend it to others. Thus, China’s rhetoric about equality in global governance is contradictory. If China's vision were to come true, the role of NATO would diminish, which would pose a major security risk for Latvia.

The Chinese see themselves as the central state in the world. In the Chinese language, the word “China” means “middle state” or “central kingdom.”

Military game simulation at the Taiwan Ministry of Defence

Military game simulation at the Taiwan Ministry of Defence

How should we in Latvia build relations with China?

China is not going anywhere. There will be businessmen who want to develop their business. There will be human rights defenders who warn against authoritarianism.

China only cooperates in areas that are beneficial to it; therefore, China is a competitor, a partner, and also a threat.

China is interested in those fields where it can learn from Europe, such as biomedicine, green technologies, artificial intelligence, IT and STEM fields, and various innovations. China’s cooperation is always a long-term strategy and is not based on quick profit opportunities. It is designed to achieve the party’s long-term strategic goals and to develop various Chinese technological innovations.

What about the future? Are you planning to return to Latvia?

I have always wanted to do so; it simply has not happened yet. At present, I have the opportunity to work, conduct research, and continue my professional development in Taiwan, and I intend to make full use of these opportunities. I sincerely hope that one day I will be able to return to Latvia.

Related news

RSU doctoral research explores the potential of medicinal plants in antibacterial therapyDoctoral Students' Stories, Research

RSU doctoral research explores the potential of medicinal plants in antibacterial therapyDoctoral Students' Stories, Research