RSU student's internship in a Moroccan hospital

Qualified doctors with sound medical knowledge who can treat thousands of patients with numerous different illnesses with insufficient funds for medicine. A lack of funding for doctors, medicine and sterilised healthcare products, filth, patients lying by the entrance of the hospital. Laura Bajāre, a sixth year student in the Faculty of Medicine at Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU) came home from her internship in Morocco with these contrasting impressions.

Why Morocco?

Laura is an active and curious student who not only studies Medicine at RSU but is also active in the Association of Latvian Medical Students (LaMSA). This organisation for young medical students offers students from the third year onwards the opportunity to undertake an annual international internship for a month. The most popular countries are Germany, Austria and other countries in Europe, but the the opportunity to practice in Africa is more enticing and unusual.

The public or state clinic, where Laura gets to learn about and get a taste of work in a Moroccan medical institution, is located in the third largest city Fez, with a population of more than a million inhabitants. In 2009 the university and hospital, built by King Hasan II, opened its doors and since then the city and surrounding region have started to develop rapidly.

Public and private medicine

Morocco has a distinct difference between public and private medical institutions. Private clinics have a high quality of healthcare, professional services, excellent specialists and essential medication, but all of this is available to Moroccans with the funds to pay for it, and foreigners. Laura was also advised to utilise the services provided by private medical facilities while another intern was taken to the hospital admissions department in another public hospital where they had to share a ward with a large family of cats. It would not be fair to claim that public clinics have unqualified medical staff that work in public clinics, yet the large wage difference means that many doctors are attracted to work in private medical institutions, so for this reason medical residents work in public clinics. During Laura's internship, one of the other residents shared that their wage was withheld for a whole nine months.

The long queues to see a doctor are surprising. What surprises one the most is not the waiting, which Latvians are familiar with, but the form it takes. Patients arrive with huge bags, blankets, pillows, rugs, roll them out by the hospital entrance door or nearby and start their waiting time – living there. The number of patients markedly exceeds the capacity of the medical staff and for this reason, one may be living near the door to the entrance for an unknown length of time. Patients with acute illnesses can see a specialist sooner. Sometimes you can hear loud wails from the entry door and cries for help which are sometimes true signs of pain, sometimes simulated to try and skip the queue more quickly.

How to avoid infectious diseases?

According to one of the surgeons, in the public clinic about 80 % of the patients end up with postoperative infections. These are caused by non-compliance with hygiene precaution during operations, a lack of sterile medical products, ignorance of the general public on a healthy lifestyle and their lack of education. Clean drinking water must be purchased, as tap water or water from wells in most regions is of poor quality and untested. As most people are poor, they don't have money for drinking water and there are frequent disputes between bottled water manufacturers and sellers. Many people develop intestinal infections which are not identified due to a lack of funds. These are treated using a wide spectrum of anti-bacterial therapies.

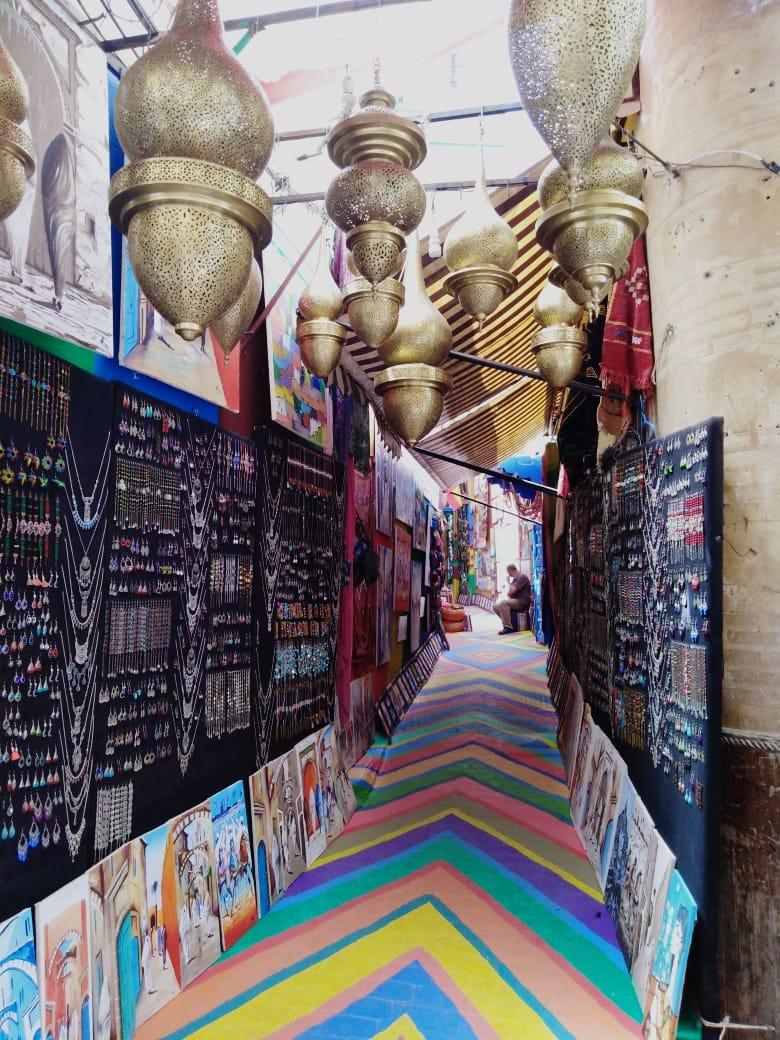

During the internship in Fez the heat reached 37C which is untypically cool for this time of the year. Families in Morocco are usually large and they live quite densely in the historical centre of Fez. For instance one could get from one end of the suburb of Medina, which has 70 thousand inhabitants, to the other in 20 to 30 minutes. In Morocco you can come across many rare genetic disorders, as marriages between close relatives are common. For religious reasons Moroccans, who are primarily Moslems, have limited opportunities for medical treatment and the true cause of illness or death is never determined. The locals also resort to self-medication as it is possible to purchase all types of medicines without prescription, except for anti-epilepsy medication and strong narcotics. Yet in many parts of Morocco where access to doctors is limited and people have meagre funds, shamanism is prevalent in the treatment of diseases and the consequences of this need to be treated in a public hospital. Often these consequences are tragic and cost the patient their life.

Distance is measured in hours

Laura tells how in Morocco, distance is not measured in hours but in terms of time. And so at Fez hospital, to cover a region that is five to eight hours away and the hospital also treats the ethnic Berber people who perform traditional face painting. In some regions of Morocco the common illnesses differ, as there has been a varied history because of Spanish and French colonisation. Sometimes in order to force the locals to submit to a power, chemical weapons had been used, which has had tragic consequences - damaging the health of the local inhabitants for generations to come.

There were 17 interns from different countries in Laura's group, for instance, from Spain, Switzerland, Norway, Turkey, Slovakia and other countries. The medics in Morocco are open and hospitable, they are happy to take on students from other countries. Laura's day started with lectures, followed by ward rounds in the paediatric ward together with local students. This was followed by conversations with the younger patients, analysis of medical histories and participation in various clinical manipulations. Local students helped to communicate with the patients, as 90 % of the inhabitants speak Arabic, but 30–50 % – in Berber languages. French is taught at school and it is spoken by approximately a third of the inhabitants. English is less commonly spoken yet most students could speak it.

Help for the younger patient

During the internship there was a disturbing and unacceptable situation. During a night shift that Laura was on together with some of the local students she was informed of a patient'e medical history. The child had already been in the clinic for 15 days and during this time a differential diagnosis had been made - either leukemia or turberculosis. The patient's situation was described as acute, with a growth delay. Xrays showed that the right lung was in full shadow while the left one still had patchy areas. The abdomen showed a large ascite or fluid buildup. Slight dehydration could be detected as the patient was told to decrease fluid intake.

Entering the ward the students noticed a frightened child who was holding on to the paediatrician's coat and breathing rapidly. The students had sat down on the child's bed and the patient had asked Laura about her home, family and pets. A person from Europe with fair hair and blue eyes was something to look at in amazement.

A few hours later and following a number of requests by the students, the decision was made to perform a paracentesis by inserting an intravenous catheter, using a standard 0,5 l plastic bottle, performed by a paediatrician. During the procedure the patient developed acute abdominal pain but there is insufficient pain medication for everyone and therefore it is administered only after evaluating the level of necessity. Although it was clear that the doctors' actions were not adequate, Laura stresses that the training of students and residents is conducted based on European guidelines and World Health Organisation recommendations.

Laura defends the local doctors who Laura says treat the large, mainly poverty-stricken Moroccan population with limited medical resources and medication as well as very limited diagnostic equipment. If the doctors were not so selfless the situation would be much more dire for the 34 million inhabitants of this country. When asked what she could take home from the experience she gained in Morocco, what could be used or adapted in Latvia, Laura immediately mentions the relationship between the student and the patient. As there is a lack of medical staff in this Northern African country, students are involved in medical treatment early in their studies. In the Latvian healthcare situation the situation is not as critical, yet Laura does view that there should be more clinical practice in the later study years.

What should you know before you head to Morocco?

Anyone who wants to go on an internship in Morocco should make sure that they are immunised against tuberculosis and hepatitis. You should know that you will have to bring along your own hand sanitisers and gloves in your lab coat. For those who are heading to Morocco for a holiday you should buy medical insurance and check on the accessibility of different clinics in the region that you plan to go as emergency vehicles are not always fully functional and public clinics are not always available. In some regions of Morocco there can be different common ailments and causes of infection so it would be advisable to find out before the trip what kind of precautionary measures can be taken beforehand to prevent yourself from getting sick. For more information on this topic – https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/morocco