How artificial intelligence is changing legal work and education: insights from the FutureLaw conference

Photos: Courtesty of Artūrs Kurbatovs

On 29 and 30 May, Tallinn hosted FutureLaw 2025, Northern Europe’s largest legal innovation conference. For the second year in a row, the event was attended by Artūrs Kurbatovs, a PhD student and lecturer at the Faculty of Social Sciences of Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU). Kurbatovs closely follows trends in legal technology and actively participates in international discussions on the possibilities and limitations of artificial intelligence (AI) in law. His participation in the conference attests to RSU’s commitment to developing legal education content that aligns with the challenges of digital transformation.

This year, FutureLaw brought together several hundred participants from at least ten countries. The platform traditionally unites legal professionals, technology developers, designers, and start-up leaders, offering an opportunity to connect, exchange experiences, and engage in joint discussions on the future of legal practice in the technological era.

The multidisciplinary composition and content of the conference clearly reflected one of its core messages – we are not all lawyers, but we all create products that help legal professionals carry out their work more effectively, accurately, and in a more user-friendly way. It is precisely this interdisciplinary approach that makes FutureLaw an important platform at the intersection of knowledge and practice.

Artificial intelligence as a tool for transforming legal work

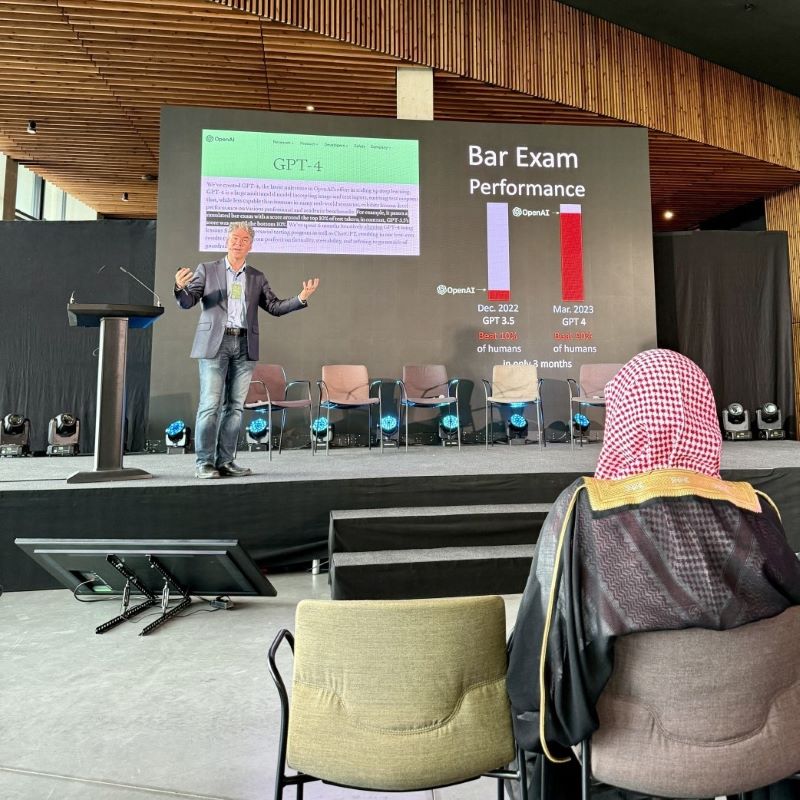

The central thematic focus of the conference was the practical application of AI in legal work and the scientific study of law. Panel discussions and practical workshops focused on the use of large language models (LLMs), document processing automation, as well as AI tools that assist in reviewing contracts, identifying risks, and developing litigation strategy. AI is increasingly emerging as an element of permanent and irreversible change – it is no longer considered an experimental technology or a solution for the future, but rather an essential part of today’s legal infrastructure.

Empirical data shows that more than half of all lawyers who have already integrated AI tools into their daily practice save up to five working hours per week, while around one tenth saves even more – up to ten hours. This increase in efficiency is not merely a quantitative improvement; it also influences the quality of professional activity and the structuring of priorities. By relieving lawyers of technically repetitive tasks, AI allows them to focus on legal analysis, developing arguments, strategic decision-making, and advising clients – all of which require professional judgement and critical assessment.

The conference offered several practical insights into the use of AI in specific legal contexts. For example, in contract review, AI can identify discrepancies between different versions of a document, flag missing clauses or inconsistent terminology, and highlight potential risks that would otherwise require time-consuming manual analysis. Large language models are also applied in regulatory analysis – particularly when comparing national legislation with European Union legal requirements or examining the evolution of case law in specific areas.

AI tools are increasingly being introduced into office practice to automate the initial drafting of documents, prepare responses to frequently asked client questions, and systematise large volumes of information. This kind of automation shifts human involvement to a higher level – focusing on reviewing AI-generated output, providing legal assessments, and adapting them to each specific case.

Similar trends can be observed in legal research.

AI helps structure collections of sources, identify thematic similarities, and provide an initial research overview, thereby allowing researchers to devote more time to interpretation and theoretical analysis.

At the same time, it is emphasised that AI-generated content still requires legal review by humans. Evaluating the accuracy, contextual relevance, and legal validity of this content remains an integral part of responsible professional practice.

Thus, the conference materials reflect a significant shift in mindset – from viewing AI as a mere technological convenience to recognising it as a contributor to professional reasoning, whose value is determined not by its technical specifications, but by the lawyer’s ability to apply it purposefully, ethically, and competently.

Artificial intelligence as an assistant, not a substitute, in the application of law

During the conference, it was repeatedly emphasised that the main challenge lies not in the accessibility of technology itself or the pace of its development, but in the ability of lawyers and researchers to integrate it into their professional practice in a purposeful and responsible manner. Artificial intelligence is no longer seen as a mysterious or uncontrollable “black hole”, but rather as a tool whose effective use depends on the involvement of qualified professionals. This requires not only the ability to select appropriate solutions for specific types of tasks, but also the competence to ensure data protection, ethical governance, and legal accuracy of content.

Such an approach requires lawyers to develop a new type of competence – the ability to combine legal knowledge with digital literacy, i.e. an understanding of how algorithms generate, structure, and present information, as well as the ability to assess when an algorithm’s output should be used as a support tool rather than a final solution. It is no coincidence that the conference also addressed the limits of AI: is it possible that, in the future, AI will provide legal solutions that no longer require verification by a human lawyer? Will the conclusions drawn by algorithms ever be able to replace human judgement in legal analysis?

Experience to date shows that, although AI can process vast amounts of information and provide structured responses quickly, its functioning relies on repeating and modelling existing data rather than creating new legal contexts or offering evaluative understanding. The essence of legal reasoning – interpreting legislation, applying it to specific situations, and constructing arguments – still demands a human presence capable of weighing the significance of facts, understanding procedural constraints, and adapting the legal position to effectively persuade the court.

Participating in the conference discussions, RSU lecturer Kurbatovs formulated this difference between humans and algorithms in a simple yet professionally significant statement: ‘The best legal advice a lawyer can give a client is advice that a judge will agree with in court.’ This idea highlights the essential distinction between text generated by AI and advice provided by a lawyer –

only a human can assess whether a particular solution is not only legally correct but also practical and convincing in the eyes of the court.

This requires not only knowledge but also intuition, judgement, and experience – qualities that algorithms are currently unable to replicate.

Thus, the conference not only confirmed the potential of AI but also reminded us of the limits within which human judgement remains irreplaceable. Professional accountability, critical analysis and legal reasoning will continue to form the integral basis of a lawyer’s work, while AI will remain a support tool whose value determined by the care and thoughtfulness with which it is applied.

Collaboration, not competition

Summarising the conference findings, lecturer Kurbatovs emphasises that lawyers of the future will not be replaced by AI tools, but will instead work alongside AI as an effective support mechanism for data selection, information structuring, and identification of relevant case law. In this model, cooperation between humans and technology is not competitive but complementary – the role of AI is to facilitate information processing and offer alternative solutions, while the final choice, its legal basis, and regulatory application remain with the lawyer, based on their professional judgement.

Such coexistence becomes essential not only in the management of legal practice but also in the content of legal education.

The experience gained and international contacts established during FutureLaw 2025 will be purposefully utilised in the development of RSU study programmes, with a special focus on technology law, data protection, and professional ethics in the context of digital transformation.

In addition, cooperation with LegalTech companies is being expanded, providing RSU students with opportunities to participate in internships, projects, and applied research, thereby creating a closer connection between the academic process and industry realities.

The conference confirmed that law is currently undergoing qualitative changes that can rightly be described as the golden age of digital transformation. AI is becoming an indispensable resource in legal practice, yet the presence of a human being – a lawyer – remains essential in the pursuit of justice and decision-making. It is precisely the ability to interpret the information provided by technology, to take responsibility, and to act in accordance with the principles of the rule of law, proportionality, and the public interest that will shape the professional identity decisive in the second quarter of the 21st century.