Kā identitāte ietekmē pētniecību. Saruna ar profesori Viktoriju Šounmī

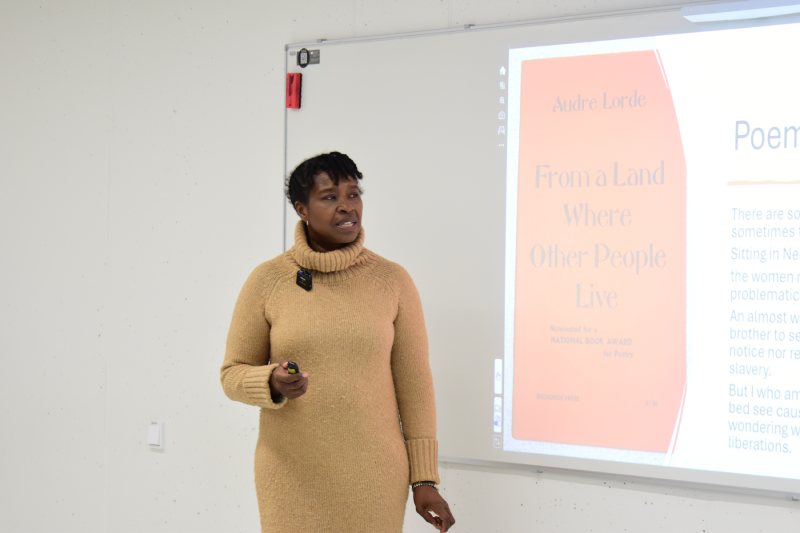

Profesore Viktorija Šounmī (Victoria Showunmi) apmeklēja Rīgas Stradiņa universitāti (RSU), lai vadītu lekciju un semināru Apvārsnis Eiropa projektā INCLUDE, kas vērsts uz dzimumu līdztiesības plānu pilnveidošanu biomedicīnas iestādēs.

Prof. Šounmī ir Londonas Universitātes koledžas (UCL) Izglītības institūta (Institute of Education, University College London) dzimuma, rases un identitātes starpdisciplinārās studiju programmas profesore un prodekāne taisnīguma, daudzveidības un iekļaušanas jautājumos (EDI). Profesore ir saņēmusi starptautisku atzinību par savu darbu, kas veltīts intersekcionalitātes, līderības un sociālā taisnīguma jautājumiem, un ir vadījusi nozīmīgas Eiropas iniciatīvas līdztiesības un dažādības jomā, tostarp četrus gadus ilgu Eiropas sadarbības zinātnes un tehnoloģiju jomā (COST) programmu par intersekcionalitāti.

Sāksim no sākuma. Kur jūs uzaugāt?

Mani adoptēja vācu un ebreju ģimene. Dzīvojām gan Somersetā, gan Devonā, bet jūs varat iedomāties viņu izcelsmi, jo viņi bija Anglijā dzīvojoši vācieši un ebreji. Tāds ir intersekcionalitātes sākums manā gadījumā.

Kā viņi nolēma jūs adoptēt?

Patiesībā es savu dzīvi sāku – ticiet vai nē – pa vilciena logu!

Piecu mēnešu vecumā mana bioloģiskā māte mani pa vilciena logu nodeva sievietei, kas kļuva par manu māti. Viņa bija bērnu aizbildne un atradās Londonā, kur tikās ar vecākiem, lai paziņotu, ka pārtrauc savu darbību. No tā laika es biju kopā ar saviem vecākiem, kuri piederēja pie sabiedrības augstākā slāņa. Vispirms mēs dzīvojām Ziemeļdevonā, Bārnstaplā, ļoti lielā mājā – tādā, kādas rāda televīzijā, ar piebraucamo ceļu un tenisa kortiem. Vēlāk pārcēlāmies uz Nezerstouviju Somersetā, dzīvojām mājā, ko dēvēja par Pulksteņmāju.

Tātad jūs uzaugāt diezgan viendabīgā sabiedrībā?

Pat ļoti viendabīgā. Es biju vienīgā melnādainā. Apmeklēju mazu ciemata skolu, kur mācījās ap 30 vai 40 bērnu, galvenokārt zemnieku bērni. Es biju ļoti zinātkārs un gudrs bērns, taču skolā bija aktīva pretestība pret to, ka es tur mācos.

Kā jūsu māte palīdzēja jums to pārvarēt?

Viņa mani īsti nesaprata. Viņa bija dzimusi 1918. gadā, un es uzrados, kad viņa jau bija gados. Tas bija tāpat, it kā par mani rūpētos vecvecmāmiņa. Viņa vēlējās izdarīt, kā labāk. Reiz, lai izskaidrotu atšķirības, viņa man iedeva dzejoli: “Flo ir balta kā sniegs, bet tu esi brūna kā šokolāde.” Viņa domāja, ka tas palīdzēs man visiem pastāstīt, kas es esmu. Jau bērnībā man piemita laba kritiskā domāšana un zināju, ka tas neizdosies. Savā ziņā manai mātei bija misionāres un glābējas uzskati: darīt labus darbus, uzskatot manus bioloģiskos vecākus un afrikāņus kopumā par barbariem.

Kā nonācāt tur, kur esat tagad?

Es vienmēr biju klases priekšgalā, bet negribēju tur atrasties, jo man nepatika uzmanība. Mana māte īsti negribēja, lai es turpinātu izglītību; viņa lika apmeklēt uzvedības un daiļrunības stundas, lai es kļūtu par kārtīgu namamāti – zinātu, kā izturēties, uzņemt viesus, pulēt sudrabu, izcept tējas maizītes jeb skones. Gluži kā filmā Dauntonas abatija. 16 gadu vecumā, sekojot savas mātes dēla šefpavāra pēdās, devos uz koledžu, lai apgūtu viesnīcu pārvaldību. Atkal biju klases priekšgalā, bet, kad mēģināju iekļūt labākajās viesnīcās kā vadītāja praktikante, durvis netika atvērtas. Toreiz mani sauca Viktorija Leina; kad ierados, cilvēki negaidīja, ka ieraudzīs kādu, kas izskatās kā es.

Tāpēc sāku docēt organizāciju vadību, īpaši profesionālo skolu studentiem, kas man ļoti patika. Iesaistījos arodbiedrībā un sieviešu iespēju attīstības darbā, vēlējos nokļūt Londonā. Kad to paveicu, mani ievēlēja par Londonas arodbiedrības Sieviešu nodaļas priekšsēdētāju.

Uz sanāksmi ierados Doc Martens zīmola apavos un džinsu jakā, gatava runāt par dzimuma jautājumiem, bet viņi teica: “Šī ir dzimumu grupa, nevis rasu grupa”.

Viņi nebija pieraduši pie melnādainas sievietes dzimumu līdztiesības jomā. Tas brīdis man izkristalizēja intersekcionalitāti – rase, dzimums un šķira pārklājas. Bakalaura grādu ieguvu gandrīz 30 gadu vecumā, pēc tam maģistra grādu un doktora grādu.

Kādā kontekstā apmeklējāt RSU?

Esmu dzimuma, rases un identitātes starpdisciplinārās studiju programmas profesore. Apzināti izvēlējos starpdisciplināro, jo varu veidot saikni ar dažādām nozarēm (piemēram, izglītību vai uzņēmējdarbību). Esmu arī prodekāne taisnīguma, dažādības un iekļaušanas jautājumos savā fakultātē, kas ir UCL Izglītības institūts. Institūts ir zināms ar skolotāju izglītību un izglītību sociālajās zinātnēs. Piedalos Eiropas projektos un četrus gadus vadīju COST programmas intersekcionalitātes atzaru. RSU ierados no projekta INCLUDE, kur es vadu UCL daļu, kas nodarbojas ar dzimumu līdztiesības plāniem (GEP) un to īstenošanu biomedicīnas institūcijās.

Vai pirmo reizi apmeklējat Latviju?

Esmu pirmo reizi Latvijā. Iepriekš neko daudz nezināju, bet esmu bijusi Lietuvā. Ar projekta INCLUDE starpniecību Portugālē, Koimbrā, iepazinos ar Diānu Kiščenko, un viņa mani uzaicināja.

Kas bija semināra auditorija?

RSU auditorija bija jaukta: darbinieki, studenti, pat daži bakalaura līmeņa studenti, kas bija ieskrējuši un satraucās, ka nokavēs lekciju. Daži studenti bija pat no Somijas, un visi aktīvi iesaistījās.

Kas bija galvenais, ko cerējāt, ka lekcijas un semināra apmeklētāji atcerēsies no tās?

Mans darbs ir kā puzles likšana. Sāku ar maziem solīšiem, lai cilvēki justos ērti savā vidē. Nolasīju īsu lekciju, kas ilga apmēram stundu, lai pozicionētu rases, dzimuma un šķiras jautājumus kā intersekcionalitātes centrālos aspektus, un pēc tam pārgāju uz semināru. Lūdzu cilvēkus iepriekš padomāt par, piemēram, tā saukto viena stāsta ideju, un atlasīt to, kas viņiem atgādina intersekcionalitāti. Es vēlējos, lai viņi padomātu, izaicinātu sevi un izprastu savu identitāti.

Ja vēlaties kaut ko darīt pētniecības jomā, vispirms jāzina, kas esat.

Runājot par to, kā to izmantot pētniecībā un projektos, ko jūs lūdzāt cilvēkus apzināties?

Es gribētu, lai cilvēki apzinās, kā viņi strādā ar datiem un kā tos interpretē, un ko tas nozīmē, rakstot pētījumus; cik apzināti viņi izturas pret neobjektivitāti un subjektivitāti.

Mēs runājām par to, kā piezogas pieņēmumi un kā intersekcionāla domāšana var šos pieņēmumus mainīt. Cilvēki atzinīgi novērtēja iespēju brīvi runāt par sarežģītām tēmām, sākot ar viltvārža sindromu un beidzot ar to, kā globālā politika un vietējās debates (piemēram, par abortu tiesībām) ietekmē pētnieku darbu, un saviem pienākumiem pret sabiedrību kopumā. Mērķis nebija parādīt vienu zelta zvaigznes apbalvojuma vērtu piemēru, bet gan radīt impulsu kolektīvām, sistemātiskām pārmaiņām, izmantojot nepārtrauktu sarunu.

Vai dabaszinātnēs ir izplatītāks uzskats, ka dati ir objektīvi?

Jā. Mans uzdevums ir mazliet mainīt šo uzskatu sistēmu. Intersekcionalitāte ir disciplīna, kas uzdod sarežģītākus jautājumus par to, ko uzskatāt par pašsaprotamu.

Kādi jauni jautājumi vai domāšanas veidi pētniekiem rodas līdz ar intersekcionālās izpratnes veidošanos?

Intersekcionālā izpratne var palīdzēt formulēt jautājumus savādāk. Kāpēc tik daudz melnādaino sieviešu mirst dzemdībās? Vai kāds uzskata, ka viņām nav nepieciešama atsāpināšana? Kāpēc menopauze ir aktuāls sarunu temats tikai tagad, kad par to runā baltādainās sievietes? Kāpēc melnādainiem vīriešiem un sievietēm vēzis tiek diagnosticēts vēlāk un tas ir agresīvāks? Vai tas ir saistīts ar piekļuvi ārstniecībai, slimības atpazīšanu vai problēmu slimības ārstēšanas shēmā? Slimības iznākumu nevienlīdzība ir pamats intersekcionālai analīzei.

Vai intersekcionalitātes īstenošana ir tikai daudzveidīgas komandas izveidošana, vai arī to var izdarīt viens pētnieks?

Daudzveidīga komanda palīdz, taču arī viens pētnieks var paveikt darbu, ja vien to dara, lai izprastu.

Analizējot ar dzimumu saistītos aspektus, meklējiet datos arī sievietes, kuras pārstāv minoritātes. Pretējā gadījumā iestrēgstat pretstatījumā “vīrieši pret sievietēm” un palaižat garām tos, kuri dzīvo šo pasauļu krustpunktos.

Tas prasa vairāk darba. Vieglāk ir lietas nosaukt vārdos un tālāk nepētīt.

Ar kādām problēmām esat saskārusies, kad melnādainie cilvēki netiek ņemti vērā?

Viens no piemēriem ir automatizēto sistēmu nespēja uztvert tumšāku ādas krāsu – neieslēdzas gaismas, nedarbojas ūdens krāns. Tiklīdz sākat šādi domāt, sekas saskatīsiet visur, arī savās metodēs un instrumentos.

Kad pieaug politiskā spriedze vai cilvēki jūtas apdraudēti, viņi bieži vien atkāpjas ierastajās pozīcijās vai ignorē savus aizspriedumus. Vai šodienas globālajā klimatā tas apgrūtina refleksīvo un kritisko darbu, kas nepieciešams intersekcionālajai pētniecībai?

Jā, un tāpēc jums jāpazīst sevi. Ja priekšā ir grūts ceļš, jūs uzvelkat piemērotus apavus. Identitātes veidošana nav izdabāšana, tā ir sagatavošanās. Mēs diskutējām par to, kā reaģēt, ja kolēģi noraida kritisko vai socioloģisko pieeju kā neīstus pētījumus, kā pamatot stabilitāti, uzticamību un ētiku, neaprobežojoties ar vienu pozitīvisma pilnu rindiņu, un kā neatkāpties no sava viedokļa, ja jūsu pieeja izskatās juceklīga.

Vai jums ir kāds padoms karjeras sākumposmā esošiem pētniekiem?

Esi tu pats. Esi autentisks. Nemēģini būt tas lieliskais pētnieks, kuru esi iztēlojies; tev ir savi izaicinājumi. Novērtē iekšējos, vietējos un starptautiskos tīklus un izmanto tos. Lasi, lasi un vēlreiz lasi. Seko savam pārmaiņu radīšanas aicinājumam. Es sevi uzskatu par drosmīgu līderi, kura izmanto līdztiesību, dažādību un iekļaušanu kā katalizatoru kultūras pārmaiņām. Taisnīgums, dažādība un iekļaušana (EDI) var kļūt par abstraktiem jēdzieniem, bet to piesaiste kultūrai maina situāciju.

Un atcerieties: pētniecība ir juceklīga. Ja piespiedīsi to sekot taisnai līnijai, nesaskatīsi patiesību.

Esiet zinātkāri un ļaujiet darbam jūs vadīt!

Saistītās ziņas

Pacientu vajadzībām pielāgotas aprūpes uzlabošana. RSU pētniece piedalās Health.Tech sanāksmē ŠveicēPētniecība, Sabiedrības veselība

Pacientu vajadzībām pielāgotas aprūpes uzlabošana. RSU pētniece piedalās Health.Tech sanāksmē ŠveicēPētniecība, Sabiedrības veselība